Last September 19th, an ambush lain in the gorge of Kamarob resulted in the death of 28 Tajik soldiers (according to official sources). A group linked to Al-Qaeda later endorsed responsibility for the attacks. This gorge is located in the Rasht Valley region, in center Tajikistan, and was a well-known stronghold of the islamic guerrillas during the 92-97 civil war. Some official sources also stated that foreign fighters took part in the ambush. This bloody skirmish follows several earlier attacks and may be the sign of deteriorating security in the country, which explains why they are taken very seriously by Tajik authorities. Those have already launched a large sweeping operation targeting the rebels that took part to the attacks, while an earlier statement (August 2nd) by the commander in chief of the Russian airborne troops lets us think that Moscow is closely watching the situation.

Tajikistan on the verge of yet another civil war?

Deteriorating security is nothing new nor surprising in Tajikistan. In 2009 already, they were concerns about djihadist fighters fleeing the Pakistani offensive and seeking refuge in Northern Afghanistan and in neighboring regions. It was thought in particular that fighters of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which had fought alongside the Taleban in 2001 and used Tajikistan to launch attacks in Uzbekistan, had returned to their former sanctuaries.

These fears came true on August 23rd 2010, when several inmates (most of them non-tajik) escaped from a high-security compound. Two weeks later, a suicide bombing targeted a militia office in Khodjent, later to be followed by another bombing against a nightclub in Dushanbe on September 6th. Finally, tajik security forces reported skirmishes with Taleban fighters in border areas on September 11th, an incident that was followed by the September 19th ambush.

Though Taleban insurgents from Afghanistan are a threat to Tajikistan's security, they are nothing more that a potential catalyzer for other risks against the country's stability. Indeed, since the end of the civil war in 1997, increasing political repression, inefficiency of a corruption-ridden state and a series of catastrophes made the country more and more unstable.

Tajikistan on the verge of yet another civil war?

Deteriorating security is nothing new nor surprising in Tajikistan. In 2009 already, they were concerns about djihadist fighters fleeing the Pakistani offensive and seeking refuge in Northern Afghanistan and in neighboring regions. It was thought in particular that fighters of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which had fought alongside the Taleban in 2001 and used Tajikistan to launch attacks in Uzbekistan, had returned to their former sanctuaries.

These fears came true on August 23rd 2010, when several inmates (most of them non-tajik) escaped from a high-security compound. Two weeks later, a suicide bombing targeted a militia office in Khodjent, later to be followed by another bombing against a nightclub in Dushanbe on September 6th. Finally, tajik security forces reported skirmishes with Taleban fighters in border areas on September 11th, an incident that was followed by the September 19th ambush.

Though Taleban insurgents from Afghanistan are a threat to Tajikistan's security, they are nothing more that a potential catalyzer for other risks against the country's stability. Indeed, since the end of the civil war in 1997, increasing political repression, inefficiency of a corruption-ridden state and a series of catastrophes made the country more and more unstable.

From the 1997 peace settlement to today's events: a balance more than ambivalent.

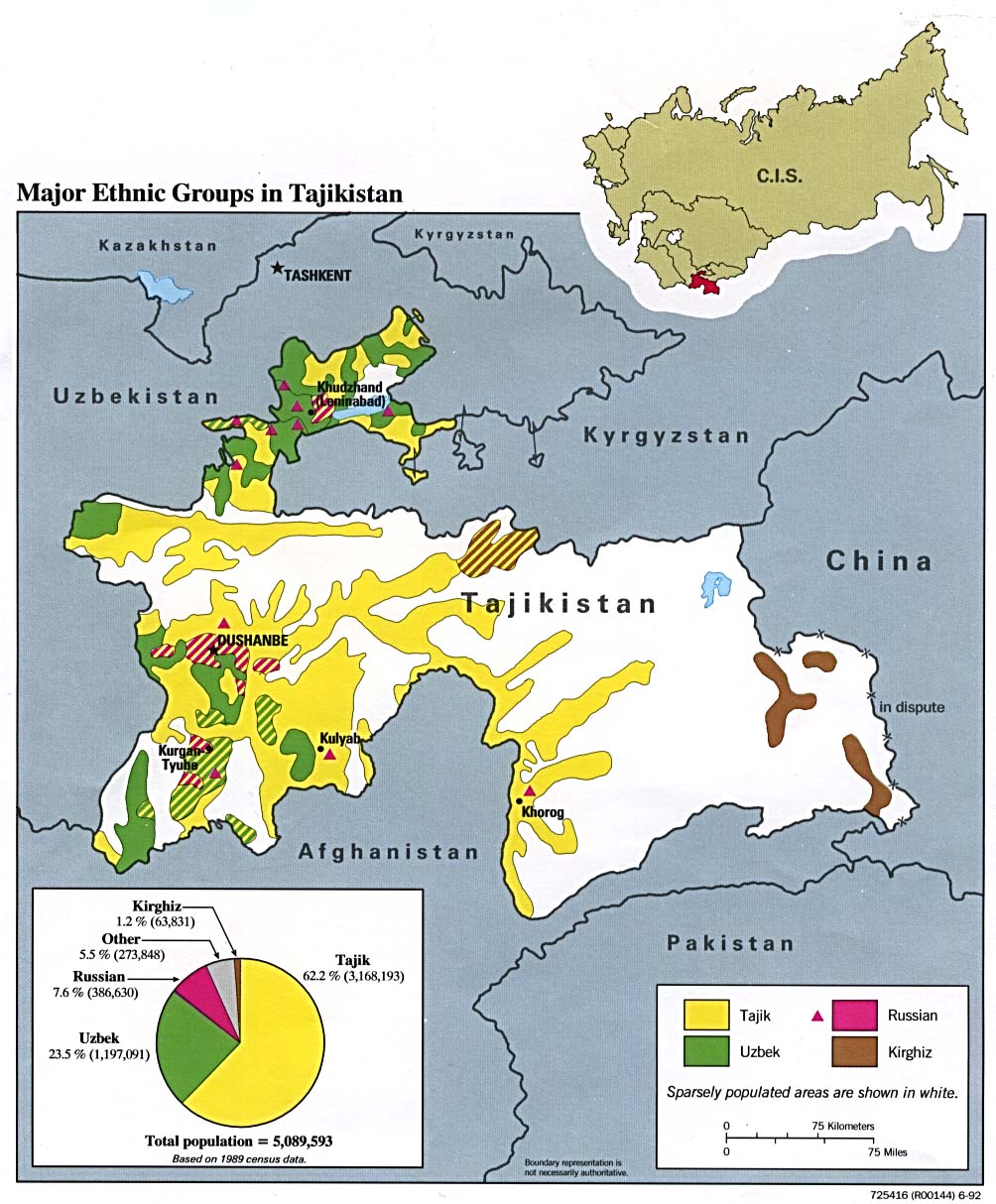

The 1997 peace agreement ended the civil war in Tajikistan between the former communist elite from the western parts of the country (Khujand and Kulyab regions) and the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), dominated by easterners(Garm and Gorno-Badakshan regions) and in which the Islamic Renaissance Party (IRP) played important political and military roles. It thus became the first (an only) Islamic political party to be tolerated by authorities in Central Asia, and to be allow to run for election. However, since then, President Emomali Rakhmonov constantly struggled to marginalize the opposition, which has almost disappeared from parliament. Furthermore, the State is now hunting down former opposition combatants (that have since then abandoned the armed struggled or have joined the official security forces) under cover of counter-narcotics operations. Finally, as in the rest of Central Asia, the repression against the Hizb-ut-Tahrir may result into parts of its members (most of them ethnic Uzbeks) to abandon this extremist yet nonviolent movement to engage in armed struggle.

Not only has the State engaged into a policy of systematic political crackdown ; it is also deeply corrupt. In particular, the efficiency and impartiality of the security forces are greatly hampered by widespread nepotism (loyalty to President Rakhmonov's clan more than skill and competence are the key to advancement). The same goes with the judiciary system, thought to be corrupt and inefficient by the local population, which increasingly turns to sharia law and mediation by clergymen to settle usual and civil conflicts like divorce. Finally, politicians and officials tend to use their position to make their personal business prosper. For example, a mysterious company, registered in the British Virgin Islands whose ownership remains undisclosed recently installed tooboothes along the Dushanbe-Khodjent road (which links the capital to the country's second city, located in the Ferghana Valley). Inhabitants and traders crossing the region have to pay a quite important sum every time they pass, which tends to exasperate them. And most of them think that those who allowed the company to collect tolls on the road are the very same in whose pockets the money finally ends...

Finally, external or uncontrolled events such as power shortages (due to tensions with Uzbekistan and poor maintenance of the power distribution system), droughts, poor harvests and the world economic crisis do nothing to improve the situation. The crisis is particularly impacting those countries like Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, heavily dependent on remittances by expat workers, whose capabilities for money transfer have shrunk. Growing insurgent activity in northern Afghanistan and the progressive criminalization of the society due to increased drug trafficking in the country also tend to have negative effects in the field of stability...

NATO, China and Russia facing a spilling-over Afghan chaos

The accumulation of all those elements is not concern-free, especially given the arrival of battle hardened Islamic guerrillas in the area. Indeed, poor quality tajik troops are not a challenge to Islamic fighters that, although they are not always familiar to the area (most veterans of the Civil War are simply too old to fight), are hardened by years of combat against NATO and Pakistani troops. There is also a real risk that the population, impoverished by the crisis and exasperated by the corruption of its leaders, turns to Islamic insurgents or drug traffickers, for financial or ideological reasons. In particular, Hizb-ut-Tahrir, which is ideologically close to the IMU, is very popular among Uzbeks, which makes this group particularly vulnerable to infiltration by islamic insurgents (one must remember that the IMU was formed by Uzbek islamic guerrillas that had already taken part to the Civil War). Thus, it would not be extraordinary to see local Islamic movements taking advantage of popular support and experience transfer from afghan rebels to become a deadly foe.

While Kyrgyzstan's stability is already greatly compromised, increased unrest in Tajikistan is the last thing the different actors with interests in the area need. NATO, for its part, has no need to see the Northern Distribution Network endangered by Islamic insurgents outside Afghanistan. China, for its part, cannot stay idle while chaos in Tajikistan threatens the stability of its own restless Sin-Kiang province. Finally, Russia, by far the most deeply concerned power in the region, cannot permit Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to slide into anarchy. By doing so, it would allow drug traffickers to operate freely from the Afghan border to the boundaries of Kazakhstan, which is to enter in a customs union with Russia by 2011. And the last thing Russia needs is tons of heroin arriving undisturbed to its border, while it already has huge problems with drug addiction among its population.